Careful The Things You Say, Children Will Listen

My Baggage Carousel Is Closed.

I have wanted to have a t-shirt made that says that. It is a saying I made up and one that I have used, often. There have also been many references to the fact that my friends come to our home and unpack their baggage and then leave it there for me to clean up. Many chances come along, every day, to make reference to the emotional baggage that we, as a race, carry on our backs, like some pack mule or camel without a choice or without a clue. Yet that isn’t the way it need be. We are the race with the brain, we are the creature with the power of reasoning, we are the animal with the freedom of choice. We know that the damage is possible, that the damage is there and that we can fix it, we can chose to live with it or that we can stop it and live a quiet life of happiness and peace.

We just don’t do it.

The damage begins when we are at our most vulnerable, when we are children. That is when we begin packing the bags which we will carry with us for the rest of our lives. As children, we don’t understand what is happening to us. We only know that we have been hurt, we have been angered, we have been ignored or underappreciated, we have felt unloved and rejected. A young person being forced to deal with these kinds of situations has not yet learned how to remain unfazed by the emotional backlash; a young person does not yet possess the strength and presence of mind to walk away, unscathed. So that small deeply significant soul collects scars and packs trunks that stay with them forever; that is, unless they are fortunate enough to grow into a spirituality, a strength, a grace that absolves them of the blame and washes away the scars.

The year of the September Eleven tragedy, while in therapy, I was able to trace most of the problems in my life back to a single event. That’s some significant development for a grown man! It appeared to me that my lifelong thirst for approval stemmed from a birthday party that happened in the first grade, in Westfield, New Jersey. The birthday boy was the most popular boy in my class, in my general grade level; pretty little blonde hair, blued boy with white skin and freckles, dimples and an angelic smile. I do not remember his name. Everyone liked him or wanted to be like him, everyone wanted to be his friend. I was like everyone else. Unlike everyone else, though, I was the only person not invited to his birthday party. I never knew why he didn’t like me, why I wasn’t invited, what was wrong with me.

How old are we in the First Grade? Six? Seven? I don’t remember but that sounds about right. I came to realize that not only did he not like me, practically nobody did. I didn’t know why, didn’t know if I had done something or if it was just the way I was, the way I acted, something that I was born with. I spent the rest of my life chasing approval from others, wondering why someone in a wide circle of acquaintances (anyone at all who appeared not to) wouldn’t like me, asking people what they thought of..you name it..my home, my cooking, my work, my outfit, my hair. Much of my life has been spent doing things I didn’t want to do, in order to make someone like me, want me or bestow upon me the gratifying sense of being accepted, of being approved of. I will state here, for the record, it has been a BORE. Fortunately, I have managed to eschew a great deal of this behaviour by (slowly!) unpacking my baggage and putting it away. There are still a few small to medium sized carry-ons in my overhead compartment.

In an interesting twist, though, last October, while on the table receiving treatment from one of my healers (Mark DeLabarre—he is WORTH having as a healer, as is his spouse, Elizabeth), a treatment that involved some regression techniques, I came to a shocking and cliché realization. It is with great vividness that I recall the struggle, the wrestling (both emotional and physical) and the words: “no….no…it can’t be…it just CAN’T be. I won’t let it be that simple, I can’t have it be that cliché. I have not spent my life trying to get approval from my father.”

It’s textbook. How many times have I sat and listened to people talk about the damage inflicted upon them by a parent? How many novels, films, television shows and personal acquaintances have touched upon feelings of negativity attached to a human being because of a behavioural pattern, because of abuse of a physical or verbal, emotional or mental nature, because of actions inflicted upon the perceived victim—even actions committed in the name of love? It’s textbook. I don’t want to invade anyone’s privacy; how can I site examples without naming names? T doesn’t have a relationship with his father at all; K’s father makes her crazy with his browbeating and disapproval; both of L’s parents left emotional scarring that cannot be escaped; M’s mother told him (recently!) that, rather than he live as a happy homosexual, she would prefer he contract AIDS and repent his sinful lifestyle on his deathbed. The only name I can use in citing examples is Pat’s because he knows, accepts and expects that as an artist I must use everything in my life and that he will be a part of almost every story I write. He also believes that we can learn from each others’ experiences and that honesty is key. I doubt that he will mind if I say that he was a fat kid growing up and that, again-in the name of love, he was often told by a family member “oh, honey, you shouldn’t eat that, you’re too fat” or “you’ve had enough to eat, you need to lose some weight”. I knew Pat’s parents before they were, sadly, recalled. No parents could have loved their child more. They were devoted to him, absolutely. They could not have known, given the era in which Pat lived as an adolescent, the damage that they inflicted upon their treasured child. In those days, parents made it up as they went along, learning from their mistakes. There was no manual. Nowadays we have manuals that people can begin reading before they meet the person with whom they will make a family. Whole corners of expansive bookstores are devoted to the art of parenting. Children are placed in preventative therapy before they are weaned, potty trained or up on two legs. Not so, when I was child. All of you folks my age or older, no doubt, have similar feelings and memories.

My mother’s father was violent man (ironically with an angelic face) who beat us. I once watched him wrap a wire coat hanger around my young (6 or 7) cousin’s throat. My father’s mother punished us by smacking us on either the head or bottom with the back of a hairbrush. This doesn’t mean they didn’t love us—I know that they did. And their corporal punishment did not leave me, in ANY way, scarred. I was the recipient of spankings, well into my teens. I am not opposed to this. It was a simple system, one in which I believed (and still do). I misbehaved. I needed to be taught my lesson. My father gave me a stern look and used a harsh voice and went for his belt buckle. As a child, I began to quake and shiver and snivel. I fought, I resisted, I cried and simpered; but eventually I bent over and took three stinging swats of the leather across my butt and was sent to my room to scream and wail until I realized that the noise did no good. Once I was in my teens, I realized the wiser, more expedient, choice was to (upon seeing the face, hearing the voice and noting the position of the hands), calmly and without protest, bend over, take the three licks and march, face devoid of expression, to my room and read a book or listen to records. It got the process over with and burned my father to see the lack of distress. I still believe in spankings and I wish that my brother and my sister would or had spanked their children with some regularity (it is not a secret that I feel my nieces need some discipline—all four of them; my nephew is still pure, untouched and heavenly to be around, even though rambunctious).

It was nothing to me, being physically reprimanded. It was a fact of life and I have, as I said, no lasting scars of either the physical or emotional kind, because of it. I also look back on my childhood with no bitterness or regret over the alternative form of punishment: being grounded or having some material possession removed from my person. My mother’s form of punishment was to take my favourite record album and break it. My mother and I closer than you can imagine and it served no other purpose than to teach me respect for people and respect for material items, when this happened. It PISSED me OFF and I learned my lessons. I didn’t have to be shown, more than a couple times, that if I broke some really important household rule, I would lose, and in a big way. After my record albums of CHITTY CHITTY BANG BANG, HIGH SOCIETY and MY NAME IS BARBRA, TWO had been (throughout the time span of a year or two) removed from my possession and snapped in half, I learned to behave myself, to mind my parents and to act with some respect. I have, since, replaced these items, on vinyl and then on cd. The lasting lessons of respect are worth much more to me than the time I spent without that music; and the lesson I learned while earning the money to replace them taught me to respect the process of getting something you want, as well as teaching me to respect money, itself. I am grateful for the lessons my parents taught me through their parenting.

A few years ago my mother told me she felt she had been a bad parent. I argued with her. I do not remember anything from my childhood (involving my parents—my school life was another matter) that is any worse than anyone else’s childhoods. Indeed, I think I had it better than the average bear. I led a priveledged life. My parents loved us and they showed us, with affection and with a general kind of spoiling from elaborate Christmases, big birthdays and lots of fun and treats throughout the school year. We weren’t horribly spoiled but we were also not terribly denied. We lived in nice neighbourhoods, went to good schools and were given the luxurious chance to see the world. No. I definitely had better than the average bear.

So where does my emotional scarring come in?

Neither of my parents abused me, emotionally. They didn’t condescend to me. They didn’t display any degree of disdain or derision (alliteration is awfully affective, isn’t it? Oh, damn, that should read ‘effective’. Oh well). No. At the end of the day, there was no psychological damage inflicted upon me from mom and dad.

INTENTIONALLY.

Remember the birthday party? Remember the chase for approval? I couldn’t get it from school mates and I certainly didn’t get it from teachers. (By the way, I recently came across my report cards from all four years of high school and read them and I have decided that teachers are SO lazy and SO uninterested in actually paying attention to each individual student that they all, each and every one of them, fall back onto this pat response that they must learn in college: ‘….is not living up to his potential…” Come on, guys! Learn a new line, that one is OLD.) I needed some kind of positive reinforcements. I needed to feel like what I was doing was right; any of it. I needed to know that I wasn’t a f*ck up. I would love to phrase that a different way but the truth is, that is exactly what I needed, growing up. I didn’t need to know that I wasn’t making mistakes, that I was doing right, that I was a good kid. I NEEDED to know that I wasn’t a F*CK UP. Teachers criticized me, school mates ostracized me. My mother’s sister, Aunt Rhonda, teased and insulted me. My mother’s mother told me that I didn’t THINK—she made a joke out if, saying that I did, instead, THIMK. She loved me and I, her, and I do not fault her for this; adults didn’t know. Dr Spock hadn’t gotten around to telling them about psychological abuse, yet.

I remember Aunt Rhonda telling me ‘please don’t sing around the house. You are a terrible singer and I can’t listen to it.’ The other one I remember is Aunt Rhonda telling me ‘you know, you could be Errol Flynn reincarnated……They say you come back as the opposite of what you were and he was perfect..he could do anything.’

I needed, desperately, to be shown some approval. There were times when my beloved mother and grandmother did this very well for me. My father’s mother and father were recalled before I could really know them; my mother’s father kept to himself—but my mother’s mother gave me whatever reinforcements she could. The one person whose approval I couldn’t seem to get was my own father. And I didn’t know why. I guess it is because he wasn’t always there. He worked a LOT. He had a big family to support and he was a big guy in the business world. I think it is from him that I get my work ethic, for which I am so proud. As a child, though, it’s obvious when your dad isn’t around. When he was around, too, he had to focus not just on the kids..he had a lot of yardwork to do, he had to spend time with mom and he had social engagements. As an executive there were many business dinners, Embassy functions, work related events; as a man, there was golf, baseball, basketball and time with friends. There were barbecues and parties and many occasions for my dad to drink too much. Looks like I inherited more than a work ethic from him. So my feelings for my dad changed over the years.

I look at photos of when I was a little boy and I see the love between us, I see the hero worship I had for him. The memories within me, of the later years of childhood, are of how much I disliked him. I was a prissy little boy listening to showtunes and divas. He was straight guy, playing sports and then sitting in front of the tv in his boxers with a beer in his hand, belching. My father is a man—always has been. I hated him for being crass and vulgar. He’s the smartest man I know. He had to see the writing on the wall. He was a marine born in Oklahoma and raised in Texas and he had a son who was going to be a fag. I imagine that was rough on him. He never let me see it, if it was. When it was important, he gave me support; the rest of the time, though, he did not hesitate to let me know when I was a source of disappointment. In my late teens and twenties, there were even a few fistfights. As an adult, I have been thrown out of his home on more than one occasion. I look back on the last forty years with my father and what I see is this:

A normal relationship. What my dad and I shared during my life has included the usually requisite of harmony and dysfunction, of love and dislike, of pride and disgust. I have hated him and he has disapproved of me. This is the relationship between fathers and sons.

As a man in my early twenties, I opened my eyes one day and said to myself ‘he won’t live forever. Are you going to go your entire life without becoming friends with him?’ On that day I began to focus on being present in his life, on sharing myself with him, on showing him the respect he deserves and the honest regard that I have for him. I hold my father in the highest of esteem and I love him, deeply. We have worked at it and become good friends, as well as relations. I am proud of us, both, and so grateful to have had our annual birthday party, reunited once more. His birthday is two days before mine and we always celebrated together—it has been years since we had the chance but last week was his 70th so I flew home for a big family reunion. It made him happy, which satisfies me.

There is, though, proof that old habits can be changed, at least old habits within me.

In what is one of the more interesting experiences of my life, I learned that I am different than I was, that my father may change but never absolutely and that honesty will always be the best course of action for me.

Sitting at the computer in my parents’ house, doing some Ebay auctioning, I chatted lightly with my dad, who was nearby watching a sporting event on television. The conversation was one that required not a lot of focus on my behalf. Until he asked me if I was working on a new book. I replied that, yes, I was working on a new book—ten in fact. He approved. He was glad. There was a caveat.

“These new books---just make them books of pictures. Don’t write all that crap you put in your last book, all that writing.”

I dedicated my first book to Pat, to my grandmother (THIMK) and to my parents. At no time did my mother or father tell me that they liked the book. At no time did they tell me that they were proud of me. I knew that they were by the way they acted, by their voices and their eyes changed when they spoke of the book to their friends (I had one or two chances to be in the room when this happened) and by their general demeanour when the subject of the book came up. When the book was published, I sent them one of the first copies and they phoned me to say thank you and I could hear the pride in their voices. I did not need to hear detailed analyses of their thoughts about the book; I got my approval by their general happiness. I know how proud they are, I do not need to have it mapped out for me—I am not that person anymore.

However, this is the first time that any detail on the book has been laid before me and I was interested that it would come out in this form. Don’t write all that crap you put in your last book.

I stopped typing and sat back in the swivel chair and looked at my father. He went on to tell me that people who buy coffee table books buy them, expressly, to look at the pictures of the famous people and not to read about the experiences of an unknown photographer. He told me, commercially speaking, it would be better for me (sales wise) if I didn’t try to make it about myself; they don’t know who I am, I’m not famous, they don’t care about me or my story. They want to look at the photos of the famous people.

I had two choices. The first was to get my feelings hurt and argue with him. The second was to let it roll. This happened on my father’s seventieth birthday. I turned to face him in the swivel chair.

“Thank you for you point of view. It’s an interesting one. You are the first person to ever tell me that; everyone in my life who has a copy of my book has complimented me on the writing. I even get fan mail from strangers who have taken my email address off of the author flap. So I had no idea that this point of view was possible. Thank you.”

He continued with his explanation, saying that which I had already heard. He told me that I would probably sell more copies of my new book(s) if I didn’t force my own thoughts and journeys on a reader who wasn’t interested.

“I want you to know that I am not hurt or angered by what you said but I should tell you that, actually, there are people who are interested. Not only have I received compliments on THE SWEATER BOOK but I have three online journals that are, I believe, well read by people who actually are interested. You just aren’t interested in reading what I write because you don’t want to know about my personal life.”

“You’re right. I don’t want to know about your personal life.”

There it was. That was it. That was the first thing my father has said to me in years with which I am prepared to take issue, to get upset. I didn’t care that he criticized my book. I didn’t care that I recorded two cds and gave them to my parents and that not only have they never listened to them, they have never acknowledged that they exist, other than to say thank you for the gift (truth is, most of my friends have not listened to them and few have offered their support or critiques and –for the most part—those who have, have offered critiques that hurt my feelings..one of the reasons I no longer ask). I have let slide many things over the years because it was simply easier to do so, rather than get into an embittered tug o war over it. I respect my father enough to allow him his opinions and I respect myself enough to not pack any more baggage on this journey.

I had to make a choice. It was his seventieth birthday. I would be there for a week.

I had to make a choice.

I let it go.

None of it was important enough to create any drama on this most special of days. I am strong. I am (at least, partially) spiritually balanced. I am a different man than I was and I accept him as he is. I accept his limitations and I love him for them and so many other things.

But I can’t help feeling sorry for him. My father doesn’t want to know about my personal life. He comes from a time and a place that make it impossible for him to accept me in my entirety. I understand that it is difficult –can be difficult—for someone of his age and with his background to accept, fully, the idea of homosexuality. I realize that he may accept that I am gay, he may accept Pat and welcome him into his home, he may be able to say the words; but he is not, never has been, and may never be completely comfortable with it. And that makes me sad. It makes me sad because this discomfort has caused him to put up walls between us. He loves me, he accepts me but he (apparently) wishes things were different. My mother tells me that he is just bothered by the fact that when I was a boy he had dreams of his beautiful son growing up and marrying a beautiful girl and giving them beautiful grandchildren. They have five beautiful grandchildren, they don’t need more. They can’t handle the ones they have. I love my nieces and nephew but they are a handful, sometimes even bratty. As far as my marrying a beautiful girl goes—I have a beautiful mate. A good and honourable one. My sister’s husband left her and their daughters for another woman. My brother and his wife have had a rocky relationship that I will not discuss here, out of respect for their privacy. Pat and I have a perfect relationship based on love, respect and trust. He saved my life, he got me sober, he supported me when I couldn’t work. He takes care of me. We take care of ourselves. We bring no stress to my parents’ lives.

The truth is, I feel sorry for my father because he SHOULD want to know about my personal life because I am an extraordinary man. As I have gotten older, what I have come to see is that the best compliment we can share with people is that we allow them to know us—to really know us. It is most important than when we have left this little planet people be able to look inside and know that the relationships we shared were real. We must share ourselves and know each other. And my father doesn’t know me. He doesn’t know that people consider me reliable, that people have respect for me as an artist and as a person. He doesn’t know that I am considered a man of integrity and honour and that I live a truly happy life, that I will never be alone and that I will achieve the elusive happily ever after. He won’t know these things because he doesn’t know me. He doesn’t want to know about my personal life.

I do not judge my father because of these facts. I love and respect my parents more than they can ever imagine. For years I have listened to other people malign their folks. Not I, said the Stephen. My parents are heroes of mine and they are going to stay that way. They are my friends and my role models, my comfort and my company. There will be no negative ramification in my mind or in my life because of my father’s admission (though we have a close friend who, upon hearing this story, agreed with my father—Pat has declared he no longer wants to be friends with this person); it is just a fact to be tucked away in the rolodex of my mind. This little episode was just an experience to allow me the chance to know him better. He has shown me that I am worthy of his honesty, however unattractive the facts may be. He has done me the honour of allowing me to know him, to really know him.

That is approval enough.

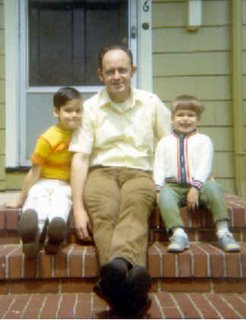

Please note that the photo fo my father, my brother and I was taken by my mom.

2 Comments:

love the aunt rhoda section , You know i love the CDs, you are magical and always have been to me . I guess it's just a father son thing.

My Aunt is a not nice person. And I know you support my work on cd--but you've always been supportive, as you always are with your loved ones, so it never surprised me a bit that you would be!

I don't know if it's a father/son thing.

We'll see...

xoste

Post a Comment

<< Home